Reviews and Press Clips for Nature Wars

Russell Baker

New York Review of Books

Feb. 21, 2013

Glancing out the kitchen window one sunny afternoon not long ago, I was startled to see two beautiful red foxes copulating in the garden. It was not the unabashed sexual display that was remarkable. Mating must be routine exercise out there, judging by the frequency with which brand-new rabbits can be seen eating the lawn, but foxes are another matter. This is an in-town garden at a well-trafficked intersection two blocks from the county courthouse, definitely not a fox-friendly location. A single fox doing nothing at all on this turf would be a newsworthy sight; two foxes engaged in propagating the species would seem to border on the unthinkable.

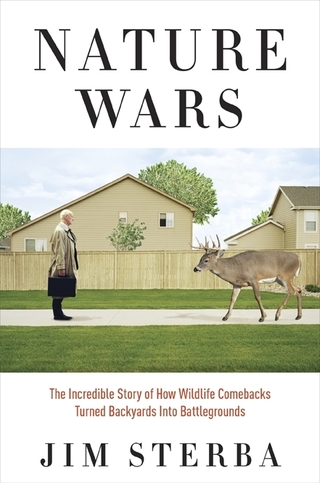

Jim Sterba, on the other hand, believes it entirely thinkable. His Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards into Battlegrounds argues persuasively that events like this foxes-in-the-garden sighting are evidence that humans are losing some kind of property rights struggle with creatures of the wild. He cites an extensive history of resolute and sometimes blatantly hostile real-estate invasion by beavers, Canada geese, wild turkeys, and white-tailed deer, all of which were once assumed to be picturesque and even lovable denizens of the dark and safely remote forest. In-town appearances by coyotes and bears are now commonplace in communities across the country, and trespassers in my own garden, aside from the foxes, have included groundhogs, possums, skunks, feral cats, and one blue heron that ate all the koi with which we thought to beautify the fish pond.

Just today, as this is written, the local newspaper has arrived with a front-page headline declaring, “Vultures Take Over Leesburg Neighborhood.” Some 250 of these valuable but socially insufferable birds, it states, have “taken over” a residential area—“stripping bark off trees, eating rubber off roofs, cars, hot tub, pool, and boat covers and destroying grills.”

In the past fifty years or less, all these woodland creatures seem to have discovered that life among the humans can be just as comfortable as it is in the forest, and the eating perhaps even easier. The woods have no garbage cans and dumpsters filled with discarded food, no lovingly tended tomato plants, no ready-to-pluck dahlias and nasturtiums, no tasty, newly planted shrubs.

Best of all from the animal viewpoint, humans are no longer the same dangerous predators who once pushed the beaver close to extinction and reduced the entire North American white-tailed deer population to a trifling 500,000 scarcely a century ago. Sterba believes that this human withdrawal from combative relations with woodland animals is one of the major causes of their proliferation: man as killer has undergone a softening change.

This kinder, softer American, Sterba notes, has only a remote relationship with the natural world he inhabits. Over a span of some four hundred years Americans necessarily cultivated a close grasp of nature’s laws and whims in order to survive the cruelty of a primordial wilderness, and to level forests, make land productive, and become competent at hunting, fishing, trapping, and animal husbandry.

Now, in little more than a single generation, this long relationship with nature has withered in a culture that finds Americans giving themselves up to the indoor ease of the technological way of life. Today’s average American spends most of the day indoors or inside an automobile traveling some hellish commuter road between workplace and home. Experience of his own natural habitat comes largely from watching beautifully photographed films on television. In Sterba’s word, he has become “denatured.”

Denaturing has produced an unrealistic and somewhat sentimental view of woodland creatures, which, as Sterba construes the situation, is one reason so many seem to feel they can trespass in our gardens with impunity.

His book, written with considerable charm and more wit than commonly found in works that deal with ecosystems, includes extensive and often entertaining treatments of such common nuisances as beavers, Canada geese, and feral cats, as well as various animal support lobbies that make life miserable and sometimes dangerous for wildlife control agents. For the denatured reader, there is a wealth of useful statistics.

Is it generally known, for example, that the beaver is the largest rodent in North America, that the adult male may be four feet long from nose to tail tip and weigh as much as sixty pounds? Or that the giant variety of Canada goose, weighing ten to twenty pounds, does not migrate but likes to settle in groups of hundreds, sometimes thousands, on golf courses and public parklands where, with their distinctively hyperactive digestive systems, they must void their bowels approximately fives times an hour? Or that the population of feral cats is thought to be somewhere between 60 and 100 million, that they have human supporters—even “national cat protection groups”—that wage bitter struggles against songbird lovers who see the wild felines as a threat to the future of beauty on the wing?

Sterba refers to human champions of this animal or that as “species partisans.” Though sympathetic to their devotion to animals and their care for the environment, he clearly disapproves of some of the tactics they employ in pursuit of their high-minded objectives. Officials of an upstate New York village planning to rid the community of an infestation of Canada geese find themselves, for example, confronted by TV crews summoned to cover a protest against a pending “goose Holocaust.” After sharpshooters are hired by Princeton, New Jersey, to cull its deer population, “the mayor’s car was splattered with deer guts and the township animal control officer began wearing a bulletproof vest after finding his dog poisoned and his cat crushed to death.” People “denatured” from their own habitat tended to treat the environment and its other inhabitants in mindless ways, unintentionally and often with the best of intentions.

Early environmentalists, like Thoreau, wrote of a landscape despoiled by ignorance and exploitation, and this narrative of loss through human meddling—the idea of “man the despoiler,” in Sterba’s phrase—still ran strongly through the last century’s environmentalist culture. Sterba writes that this idea led to the notion that the natural world “was a benign place” where wild creatures lived harmoniously among themselves, and only man was vile:

This idea was in striking contrast to the amorality of a Darwinian nature that was indifferent and random, its creatures living in a world of predators and prey, struggling to eat, reproduce, and survive. In a benign natural world, wild animals and birds not only got along with one another but were often portrayed as tame and peaceable, with human habits and feelings.

This, in exaggerated form, was the world of faux nature packaged for delivery to people who wanted to believe that animals were just like us. Bambi and Lassie are two of the best-known practically human specimens that warm the popular heart. Those who seek something closer to Darwinian reality may prefer Bugs Bunny.

Though tightly focused on the resurgence of wildlife, Sterba’s book is basically about the recent extraordinary changes in the American landscape, the rapidity with which they happened, and how intimately they were interlocked. He defines the major events as the regeneration of the nation’s great eastern forest, the “slaughter and comeback” of its wildlife, and the spread of human population from urban concentration into suburban, exurban, and rural sprawl. His study is confined largely to the vast American deciduous forest land between the Atlantic Ocean and the prairie flatland, where approximately two thirds of Americans now live.

During America’s first 250 years, early settlers cleared away some 250 million acres of forest. Yet the forest comes back fast. By the 1950s, one half to two thirds of the landscape was reforested. Most of us now “live in the woods,” Sterba writes. “We are essentially forest dwellers.” The new forests “grew back right under the noses of several generations of Americans. The regrowth began in such fits and starts that most people didn’t see it happening.”

Why did it happen? For one thing, because oil, gas, and coal replaced wood as the major fuel for heating and cooking. Because new building techniques and materials reduced wood’s importance to the construction trades. And because the family farm began to vanish, leaving the abandoned acreage to follow earth’s natural impulse, which is to produce wild grasses, weeds, bushes, shrubs, and small trees that turn into big trees.

Then, of course, even the bleakest urban areas may yield to a civic impulse to primp a bit with touches of greenery, as in New York where 24 percent of the city’s area is now covered by a canopy of 5.2 million trees. Nationally, Sterba reports, tree canopy covers about 27 percent of the urban landscape.

A lot of this regenerating forest is included in what Sterba calls “sprawl,” a new kind of communal development created by the fateful American decision to let the automobile shape our lives. With the car’s ability to transport a commuter rapidly over considerable distances, human habitations have sprung up in scattered settings, ever more distant from cities—deeper in the woods, as it were. As this motorized workforce flung people outward, the scattering population began to produce new, smaller workplaces—little urboids, too small to be cities, too lifeless to be towns. Bursting forth here and there in the spreading nowhere, they produced “exurban sprawls that have broken free of the gravitational pull of the cities and now float in a new space far beyond them,” as David Brooks has written in The New York Times.

Sterba says that sprawl “can include suburbs, exurbs, golf courses, cropland, pasture, parks, highway median strips, parking lots, McMansions, Burger Kings, and people.” Though not officially defined as forest, sprawl areas, he says, are so covered with trees that they “have the feel of a forest,” and for many wild creatures all the comforts of forest home. In short: ideal territory for a wilderness creature struggling to flourish after a brush with extinction. Hence, foxes in the garden, beaver dams flooding the soccer field, geese emptying their bowels in the old swimming hole, coyotes biting faithful old Rover, and Bambi’s ungulate kin crashing into three thousand automobiles every day.

These creatures that once delighted us by remaining remote and shy of human company have lately changed from remote to chummy, from shy to importunate. For many they have begun to seem just another variety of pest; for some, they are simply menaces. Geese, for instance, have lost many devotees since several were sucked into the engines of a jet departing LaGuardia Airport, in January 2009, and forced an emergency landing on the Hudson River, which 155 people survived only because of the extraordinary skill of pilot and crew.

It is the white-tailed deer, however, that dominate all discussion of wilderness creatures versus human society. This may be because there are simply too many deer for their own good. Sterba’s figures indicate that as recently as 1900 all of North America had a deer population of perhaps 500,000. I recall the excitement of seeing a deer standing perfectly still on a northern California mountainside in 1956. Seeing a deer at all in those years was a thrilling event. Now it is likely to be merely irritating, if not downright alarming.

Vincent J. Musi/National Geographic Stock

Feral cats in the Westport neighborhood of Baltimore, 2010

By the 1990s the deer population had exploded. Various estimates for the United States put it at 25 to 40 million and growing unchecked, and apparently uncheckable. By 2006 this vast and scattered herd was being called “a mass transit system for ticks carrying Lyme disease.” Sterba’s figures put deer damage to farm crops and forests at more than $850 million; the deer had eaten $250 million worth of landscaping, gardens, and shrubbery. By eating plants that grew under large trees they damaged songbird habitats and put certain bird groups at risk.

“But threats to forests and songbirds paled in comparison to the whitetail’s menace to people in the form of collisions of deer and motor vehicles, which were occurring at a rate of three thousand to four thousand per day,” according to Sterba. “The toll of cars crumpled, people killed and injured, Lyme disease contracted, gardens destroyed, crops eaten, and forests damaged,” he writes, justified The New York Times’s editorial conclusion that “white-tailed deer are a plague.”

Sterba lists several factors that made “such beautiful creatures become so much trouble.” These include a lack of predators, a decline in hunting, changes in habitat, mismanagement by state wildlife agencies, and human sprawl.

Whitetails are “quick studies,” he writes. It took them very little time to discover that “people who have sprawled across the landscape aren’t the predators they used to be.” The sprawl people brought with them attitudes that created ideal conditions for a whitetail explosion. Sprawl culture with its “exurban subdivisions, big-box houses on multiacre plots, weekend places, second homes, hobby farms, and even semiworking farms” created “a mosaic of hiding places, open places, feeding places, watering places, bedding places.” Moreover, sprawl people grew many plants they did not eat, harvest, or market. Using “prodigious amounts of fertilizer, water, and hired labor, they grew plants mainly to look at.” They created “deer nirvana,” a wildlife biologist said.

Then, says Sterba, they made one last crucial adjustment: they cleared the landscape of the last major deer predator remaining: themselves. Most did not hunt. They posted their property with “No Hunting” signs and passed laws against discharging firearms that effectively put large areas of landscape off limits for hunting:

Suddenly, for the first time in eleven thousand years, hundreds of thousands of square miles in the heart of the white-tailed deer’s historic range were largely off limits to one of its biggest predators. Suddenly, an animal instinctively wary of predators, including Homo sapiens, found itself in a lush habitat where major predators—drivers being the exception—didn’t exist.

Thinking of possible ways to avert a disaster in deer–human conflicts, Sterba imagines a return of the human predator. He writes of “professional” hunters who are seen as “new saviors” in some suburbs where sharpshooters are hired to kill deer and are paid with tax dollars. He describes a proposal to have professionals train local hunters to become “urban deer managers,” with the costs offset by selling venison in farmers’ markets. “It seems like a good solution,” he concludes, “but it probably won’t happen anytime soon.”

Copyright © 1963-2013 NYREV, Inc. All rights reserved.

CHICAGO TRIBUNE.

By Donna Seaman

9:19 p.m. CST, November 11, 2012

The drive from the Upstate New York airport to my parents' house took longer than the flight from Chicago, and I was elated to finally be in sight of the house. But the driveway was occupied by deer. Five elegant young does turned their large, deep, dark eyes on us with the disdain of teenagers annoyed at being interrupted. We gazed back, simultaneously thrilled by the proximity to such beautiful animals and impatient to park and stretch our legs. The deer flicked their tails, swiveled their ears, nosed the ground and slowly, grudgingly, sashayed onto the grass.

As we extracted ourselves from the car, they gracefully promenaded across the lawn, slipping in among the trees along a busy street that funnels traffic onto Route 9, the heavily traveled highway that parallels the Hudson River.

Jim Sterba, a distinguished foreign correspondent and national affairs reporter who was in the thick of things in Asia during and after the Vietnam War, escapes New York City on the weekends to stay in Dutchess County, not far from where I grew up. Sterba's first book, "Frankie's Place," is a memoir about courting and marrying his wife, the journalist and author Frances FitzGerald, whose own account of the Vietnam War, "Fire in the Lake," won the Pulitzer Prize. His second book, "Nature Wars: The Incredible Story of How Wildlife Comebacks Turned Backyards into Battlegrounds," is about why herds of deer now occupy our driveways and yards, eating our flowers and plants.

Sterba begins "Nature Wars" with an impressive roll call of all the wildlife he and his wife see around the cottage they rent on a former 180-acre dairy farm. As I read this census, I find myself nodding. Even in our Poughkeepsie neighborhood, we see lots of different songbirds, woodpeckers, chipmunks, squirrels, deer, wild turkeys, rabbits, woodchucks, coyotes, foxes, raccoons, beavers, ducks, eagles, turtles and blue heron. But there was no such cavalcade of wildlife when I still lived at home, back around the time I read Rachel Carson's "Silent Spring."

This fall marks the 50th anniversary of Carson's galvanizing exposé of the "sinister" effects of DDT and other chemical pesticides that were in widespread and wanton use following World War II. Carson's now classic book of warning begins with "A Fable for Tomorrow," which presents a world in grim opposition to the vitality Sterba describes.

"There was once a town in the heart of America where all life seemed to live in harmony with its surroundings." Carson describes "prosperous farms," wildflowers, trees, an "abundance and variety" of bird life, streams full of fish, deer and foxes, all abruptly transformed when "a strange blight crept over the area ... a shadow of death." Animals, people, plants and trees began to sicken and die. "There was a strange stillness." What caused this catastrophe? "No witchcraft, no enemy action had silenced the rebirth of new life in this stricken world. The people had done it themselves."

Carson's clarion book has been compared to Harriet Beecher Stowe's "Uncle Tom's Cabin" in terms of its role as a catalyst for social change. The environmental movement did coalesce in the wake of "Silent Spring," and laws were passed to protect endangered species and the air, water and land that sustain all of life. Even so, environmental threats continue to multiply. The battles to protect wetlands, forests, rivers, oceans, public lands and wildlife against pollution, destruction, decimation and global warming rage on. Environmental writers continued to sound the alarm. Carson wrote that science and literature share the same mission, to "discover and illuminate truth," and her intrepid and eloquent followers are many, including Gretel Ehrlich, John McPhee, Wendell Berry, Terry Tempest Williams, Barry Lopez, Rick Bass, Barbara Kingsolver, Rebecca Solnit, Michael Pollan, Bill McKibben, Carl Safina, David Quammen and Elizabeth Kolbert. Yet there have been some phenomenal improvements. The facts about wildlife resurgence that Sterba present in his mind-bending dispatch from the new world of "people-wildlife conflicts" are startling and staggering.

Remember the coyote who sauntered into a downtown Chicago Quiznos? The cougar Chicago police shot dead in Roscoe Village? Consider the more routine animal nuisances: herds of garden-devouring deer, gaggles of excreting Canadian geese and battalions of beavers busy chewing down cherished trees and building dams that cause infrastructure-damaging floods and even disrupt "the water flows around electrical power generation facilities." We have sprawled into animal terrain, building houses, malls, corporate parks and golf courses, and now, Sterba writes, "critters have encroached right back." And why not? We have enhanced their habitats and eliminated predators — although we do accidentally kill an appalling number of animals with our cars, and millions of birds die in collisions with high-rise windows. Filled with wonder over the beautiful animals that are now all around us, we feed wild birds (supporting a hugely profitable bird seed industry) and even coyotes and bears, inviting deadly attacks. And don't get Sterba started on the subject of feral cats.

It is exciting to see wildlife. Consider, there were no deer left in Illinois, Indiana and Ohio by the late 19th century. No beavers anywhere. Restocking and restoration efforts have been a tremendous, resounding success. We owe profound thanks not only to environmental writers, but also to all the unsung biologists, environmentalists, policymakers, attorneys, grass-roots activists, government staffers and politicians who ensured that we averted ecological disaster 40 years ago. But just as we had no clue as to what havoc we were unleashing with the use of DDT, we have not been aware of the consequences of renewed animal populations. We've even been oblivious, Sterba tells us, to the return of the trees. The halt to deforestation in the late 19th century initiated an era of luxurious regrowth. Citing tree counts and aerial survey, Sterba asserts that we are all, in essence, forest dwellers now, even those of us who live in the heart of big cities. Trees support wildlife.

Sterba is ferociously well-informed and lucid in his chronicling of "how we turned a wildlife comeback miracle into a mess." His book is a tale of noble intentions and unintended consequences, ignorance and aggression, idealism and irony, reality and responsibility.

Here's one example of the many Sterba considers. Pulitzer Prize-winning political cartoonist Jay Norwood Darling — nicknamed "Ding" because he "regularly dinged (President Franklin D.) Roosevelt" — was also "an ardent and knowledgeable conservationist." So FDR appointed him to a committee formed to figure out a way to restore the country's imperiled waterfowl. Also on board was Wisconsin-based Aldo Leopold of "A Sand County Almanac" fame, the man who founded the profession of game management. Leopold's paradigm-alerting land ethic, as he explained, "changes the role of Homo sapiens from conqueror of the land-community to plain member and citizen of it." This crucial land ethic also "enlarges the boundaries of the community to include soils, waters, plants, and animals, or collectively: the land." A vision to live by.

Roosevelt then appointed Darling director of what would become the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (for which Carson later worked). Darling proved to be a formidable and effective protector of ducks and geese, so much so that his agency inadvertently established the very conditions that nurtured today's immense population of "nuisance" Canadian geese.

So we find ourselves in a quandary. American wildlife has rebounded from near-extinction to overabundance, and many of us recoil from the need to cull animal populations.

How easy it is to hold fast to outmoded assumptions, to grow rigid in one's perceptions, to tune out the "other side." Thoroughly researched and powerfully written books such as "Silent Spring" and "Nature Wars" induce us to question our thinking, opinions and values. It's one thing to argue that animals are sentient beings and that we should never abuse or unnecessarily kill them. It's another to allow naïve and wishful fantasies about wild animals to cloud our understanding of what's at stake when nature gets out of balance, even if it's thanks to our interference, however well-intentioned. We are going to have to figure out how to live safely with all those amazing and, yes, precious, deer, geese and beavers, those coyote and cougars and bears.

Donna Seaman is a senior editor at Booklist and editor of the collection "In Our Nature."

Copyright © 2012, Chicago Tribune

BARRON'S, Dec. 7, 2012

Nature Wars by Jim Sterba. Well worth the effort if you are engaged in conservation issues. Sterba starts his book on the borders of Maine’s Acadia National Park. Seeing some grapevines choking off a ravine and stream, Sterba rips out the interloping vines so the original forest can take hold. But his research reveals that the vines were probably planted in the 19th century, when the entire area was bucolic farmland. John D. Rockefeller Jr. bought the land, which was turned over to Acadia in 1961, and a new forest devoured the pasture that existed before.

That is the thesis of this book: The major annihilation of nature in the U.S. occurred in the late 19th century, when everything from buffalo to hardwood forests was felled wholesale. The conservationist efforts of the past 100 years have been so successful that wildlife such as coyotes, turkeys, bears, and deer — not long ago a sight so rare that Americans stopped their cars to get a look — have become plentiful pests. At times this book reads like a well-reported tabloid exaggeration, but it will surely make you look differently at the “narrative of loss” at the heart of our environmental news coverage.

THE LOS ANGELES TIMES:

Nature Wars' details an uneasy relationship

Jim Sterba takes a thoughtful look at Americans' widespread and enduring ignorance of the natural world.

By Hector Tobar, Los Angeles Times

Dec. 7, 2012

________________________________________

The nature-challenged reader will discover many new and startling facts in Jim Sterba's new book. Among them all one stands out: Not only are America's Eastern forests roaring back to life, they've been doing so for more than a century.

Sterba, a veteran reporter for the Wall Street Journal and New York Times, literally stumbles onto this truth one day amid the majestic trees of Maine's Acadia National Park. He sees feral grapevines strangling a birch tree. When he gets out of his car to rip the vines out, he finds a rusting 1927 Maine license plate.

After talking to the locals, Sterba realizes he's walking on the ruins of a farm that's been swallowed up by a new forest. The grapes were there before the trees, "a remnant of a very different civilization that had existed not long ago."

In some of the more densely populated corners of New England, trees have been filling up abandoned farms since the 1850s. Now armies of cute and cuddly creatures are filling up those forests too, including white-tailed deer. So many deer, in fact, as to become odious and obnoxious.

Sterba's book is a much more sweeping and thoughtful work than its unwieldy and tabloid-sounding title would suggest. At its best, "Nature Wars" isn't really a book about the conflict between man and nature. Nor is it about the clashes between those who defend nature and those who seek to manage it. Instead, it's best read as a history of Americans' widespread and enduring ignorance of the natural world and how that ignorance has created new and strange ecosystems — especially in our sprawling suburbs and exurbs.

Consider, for example, the weird, epic saga of the largest rodent on the continent, Castor canadensis, otherwise known as the North American beaver. Beavers were wiped out in Massachusetts by frontiersmen and Indian trappers and traders in the early 18th century — they never coexisted with European settlers.

But in 1928 they returned to western Massachusetts as the descendants of 34 beavers from Canada released in the Adirondacks a few decades earlier. Sterba shows how beavers soon thrived in resurgent forests now largely free of their old predators — including humans, no longer interested in slaughtering them en masse for the fur trade. By 1996, the state's beaver population was estimated at 24,000.

Those beavers now live amid strip malls and golf courses. "People and beavers were sharing the same habitat as never before," Sterba writes. "They had similar tastes in waterfront real estate. Both like to live along brooks, streams, rivers, ponds and lakes with lots of nice trees nearby."

Sterba relates the story of the beaver and other troublesome wild creatures with wit and impressive reportorial diligence. He shows us how new suburban residents plant pretty trees in their yards, only to see the beavers chew them down to build dams that flood those yards.

The recent natural history of North America is filled with such stories. In Sterba's often amusing narrative, species such as the wild turkey are cast in the role of victims in one era, only to reappear as pests in another.

Like human history, bird history repeats itself — the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce.

In "Nature Wars," Canada geese disappear across the U.S. as their habitat perishes thanks to human development. But they come back thanks to human restoration efforts and to hunters who breed them as live decoys to shoot other birds. Soon much of America from the Great Plains to the Eastern Seaboard is filled with geese.

Unlike their ancestors, however, many of these modern-day geese refuse to migrate. Why should they? In the ensuing century, Sterba writes, humans had created a goose paradise filled with "… soccer fields, playgrounds, and parks, all planted in what happened to be the favorite food of Canada geese: grass."

The geese are pretty to look at and defended by geese lovers — who face off with geese detractors fed up with the birds' disgusting droppings and by their annoying tendency to clog jet engines and cause planes to crash.

One lesson Sterba draws from all this fraught history is that Americans have forgotten how to be stewards of the natural world around them. We Americans don't understand nature in the same way that Sterba did when he was a boy growing up on a Michigan farm in the 1950s; Americans today have become so immersed in "virtual reality," he writes, that they prefer to have "the natural world delivered to them on a digital screen." Even their house cats are "denatured" — back on the farm, he says, cats had real, honest "work" to do.

Not only are these facile points, they conveniently ignore that Sterba grew up during a time when rural people continued to radically alter their environment. Among other things, they sprayed their fields with pesticides that wiped out songbirds and nearly caused the bald eagle to become extinct. Nor are all the current-day defenders of wild turkeys, beavers, feral cats, white-tailed deer and other "nuisance" animals the shrill, misinformed and naïve people Sterba repeatedly makes them out to be.

"The screamers I can handle," a man who traps feral cats tells Sterba, referring to cat lovers. "It's the quiet ones you have to watch."

Beyond such predictable characterizations, there's a lot in "Nature Wars" for the reasoned and concerned human to learn about the changing natural landscape.

White-tailed deer, Sterba shows us, thrive in the faux rural, predator-free zones of many an American exurb. He paints a vivid and memorable portrait of these new eco systems, where only one, plentiful species is capable of bringing balance and harmony among living things: homo sapiens.

hector.tobar@latimes.com

AUDUBON MAGAZINE, Nov. 2012.

Whether it’s deer in the backyard or raccoons in the chimney, nature is making a comeback—in suburbia. In his new book, Nature Wars, reporter Jim Sterba explores how, ironically, many Americans are living closer to nature than ever before—and how ill-equipped we are to deal with it. After centuries of uncontrolled hunting and clear-cutting devastated ecosystems, the environmental movement inspired people to try to restore some kind of natural balance. While conservationists have unquestionably made incredible strides, Sterba argues that, close to home, we’ve overcompensated, paving the way for wild creatures to live in our lushly landscaped environs—with plenty of food and protection—but not in harmony. Beavers flood septic systems, deer devour plants, and black bears forage in our trash bins. At the same time, some suburbanites shy away from management strategies such as hunting and trapping—activities that, along with enacting ordinances to ban feeding wildlife and requiring that trash be stored in more secure bins, can help municipalities overcome this growing problem, Sterba argues. "Groups have to come together to find ways to manage the natural space where they live for the good of the ecosystem as a whole and not simply one overabundant or problematic species within it."

THE WALL STREET JOURNAL, Nov. 17, 2012.

By Stephen Budiansky

As a reporter covering the anti-hunting movement for The Wall Street Journal in the 1990s, Jim Sterba got to know quite well the many activists he terms "species partisans." There were the feral-cat zealots, who labeled a scientist a "cat murderer" when he simply published a study showing how many millions of songbirds are killed each year by the nation's free-roaming felines. There were the deer devotees, who held a vigil and lighted one candle for each of the 576 deer—"my closest friends," said one activist—killed in a controlled hunt at Quabbin Reservoir in western Massachusetts. And there were the Canada goose protectors, who turned out with a television crew in tow to decry an impending "goose Holocaust" in Clarkstown, N.Y., when town officials proposed culling hundreds of the birds, which had become a major nuisance.

None of these activists were exactly publicity-shy. But a funny thing happened on Jan. 15, 2009. That was the day that United Airlines Flight 1549 struck a flock of geese on takeoff from New York's LaGuardia Airport, lost both engines, and was piloted to a near-miraculous safe landing minutes later in the Hudson River by Capt. Chesley Sullenberger.

Expansion of suburbs into forests has created ideal habitats on their margins for deer, who are drawn into backyards and cul-de-sacs by abundant food.

Overnight the goose activists melted away. "As a journalist, I had been in contact with some of these people for years," Mr. Sterba writes. "They were eager for public attention. After Flight 1549, they stopped answering my emails and returning my phone calls." Since then thousands of geese around airports have been rounded up and euthanized with scarcely a word of protest. "Geese Gassed? Good!" ran a headline in the New York Post.

The rise and fall of goose activism epitomizes the contradictory American attitudes toward wildlife and nature that Mr. Sterba documents in "Nature Wars."

On the one hand, as Americans grow ever farther removed from the farm and the rough realities of wresting their subsistence from nature, they have begun to apply the same relentless anthropomorphism to animals in the wild that has long characterized their relationships with cats and dogs. Spurred by canny marketing that encourages people to look upon wild birds as "outdoor pets," the bird-feed business is now a $5 billion industry.

On the other hand, major changes in both settlement patterns and ecology are bringing humans and wildlife populations into ever increasing conflict: Another booming business these days is "nuisance wildlife control companies." It is the perfect irony, Mr. Sterba notes, that spilled seed from bird feeders is a significant cause of the trouble, attracting skunks, raccoons, rats and even black bears that drive frantic homeowners to call in "control experts."

Underlying it all is a shift in agriculture over the past century to high-yield production, especially in the Midwest, allowing sprawling residential development to invade what was once farm land. "Where do most people in the United States live? They live in the forest," Mr. Sterba observes. More than 100 million acres of forests have regrown on what were once cleared farm fields in the eastern United States. The changes have not only brought people in contact with wildlife but also produced ecological conditions that favor a number of species whose populations have unnaturally exploded—deer, most obviously, but also beavers, geese, turkeys, moose and bears. People feel the impact—literally, in the 3,000 deer-car collisions per day. But so do threatened bird and plant species, whose habitats are being wiped out by ravenous herds of famished deer.

In recounting a series of clashes over wildlife management in recent decades, Mr. Sterba shows that policy makers who aim to address these problems frequently must resort to hypocrisy and deceit to navigate the morass of public sentiment. Princeton Township, N.J., offers a vivid case in point. There, a proposal to allow limited hunting as a way of keeping the deer herd in check produced predictable outrage, including a death threat to a local official. Eventually the town hired a professional company that specializes in suburban deer control, their major selling point apparently being that, unlike a bunch of yahoo hunters, they do the dirty work invisibly, shooting the deer at night using silencer-equipped rifles with infrared telescopic sights. "Afterwards, they gathered up the carcasses, along with bloody leaves and other debris, leaving no evidence of the cull," Mr. Sterba writes.

Evasion and wishful thinking routinely trump scientific understanding in the stories Mr. Sterba investigates. In Massachusetts, rapidly growing numbers of dam-building beavers have flooded basements and septic tanks, contaminated wells, and undermined utility towers and railroad embankments. In 1996 the Humane Society of the United States launched a successful referendum campaign to ban the use of lethal traps to catch beavers in the state. Wildlife officials tried to point out that the ban would simply "turn what were valuable resources harvested for fur into pests to be eradicated at taxpayer expense." They also called attention to the incorrect statements that trapping opponents had made in advertisements supporting the misleadingly named "Wildlife Protection Act." In response, the Humane Society complained that the state wildlife division was violating the law by "lobbying." State election officials ordered the agency not to issue any further statements.

The result has been exactly what the experts warned. Trappers were driven out of business, and beaver numbers soared. A few former trappers, however, have reinvented themselves as "professional wildlife damage controllers," charging local governments $150 per beaver for removing "problem" animals. Instead of using the now-banned lethal traps that instantly dispatched a beaver, they have to employ cumbersome and supposedly "humane" live traps that hold the terrified animal for hours until it can be retrieved, bashed on the head and disposed of.

Mr. Sterba is particularly good at untangling the complex politics and strange alliances that have formed in these battles. Birdseed companies, outraged that federal and state wildlife agencies had (correctly) advised against using seed mixtures containing grains that birds simply discard, fought back by going after the agencies' funding. In 1996 they scuttled a plan that would have provided new revenue sources to the agencies to make up for dwindling fees from hunting licenses. Deer hunters and deer lovers have more than once joined forces to sabotage scientifically grounded management proposals, such as banning the winter feeding of deer. Meanwhile, bird lovers and bird hunters have joined hands in support of the eradication of feral cats.

The larger theme of "Nature Wars" is that even the most pristine-looking landscapes have been shaped by centuries of human occupation and continue to be altered, often radically, by the unplanned perturbations brought about by humans: marauding pet and feral cats; garbage Dumpsters that make life a breeze for bears; suburban sprawl that creates forest-edge habitat ideal for deer. The hordes of nonmigratory geese found along the East Coast today, far from being natural, are the descendants of birds captively bred a century ago as "live decoys" by hunters, who used to blast huge flocks of birds with cannons loaded with shot. Mr. Sterba argues that humans are now responsible for managing the mess they have made, whether they like it or not.

"Nature Wars" suffers some from its journalistic origins. The writing is clear though never exactly eloquent. A few strained attempts at writerly turns of phrase—Americans, the author writes in the introduction, have substituted "a great deal of real nature with reel nature"—fail to come off. And Mr. Sterba isn't always good at synthesizing his generally excellent reporting into sharp conclusions.

At the end of the book he somewhat lamely suggests that the solution is for all of us to get off our couches, get outdoors and learn more about nature, which is fine but a bit like suggesting that if only people were smarter they wouldn't do such dumb things. And, alas, his own book offers plenty of evidence that the fantasies about nature and animals sustained by modern American society are robust enough to survive even considerable contact with the real thing.

—Mr. Budiansky's books include "The Bloody Shirt," "The Nature of Horses" and "Perilous Fight: America's Intrepid War With Britain on the High Seas, 1812-15."

WHAT THEY SAID ABOUT FRANKIE'S PLACE:

A New York Times notable book.

Chicago Tribune best list for 2003.

An American Bookseller's Association Top Ten for Valentine's Day 2004.

"This little book is the 'find' of a year fraught with death and taxes and 21st century uncertainty." - Columnist Liz Smith

"If this were a movie, it would feature Bogart as Sterba, a no-frills journalist courting Hepburn, as FitzGerald, the high WASP dame who types on an old Remington and starts each day with a dip in the icy brink." - Portland Phoenix

"Frankie's Place could be a complex rebuttal to the theological concept of this Earth as a vale of tears." - Washington Post

"A fetching account." - The New York Times

"This is a beautiful memoir..." - Publishers Weekly, May 12, 2003*

"The perfect summer read..."

- Kirkus Reviews, May 1, 2003*

"A highly entertaining tale of love, family and place written with grace and lyrical humor. It took me places I hadn't expected to go, well beyond the screen doors, front porches and bracing waters of coastal Maine. I loved it." - Tom Brokaw

"And so what category does this delightful book fall into—travel book, cookbook, journalistic memoir? In the end it doesn't matter: Frankie's Place is charming, funny, full of insights into the way we live today, and it's the story of one man's lifelong search for a home."

—David Halberstam

"Jim Sterba has found his own American Arcadia, his own Walden pond, and in the process, himself. He records his quest with a loving honesty, never sentimental, never cloying . . .a man taking stock of his life at a certain time of life. What's more, it includes recipes for some delicious grub."

—Morley Safer

"A memoir almost audacious in its normalcy: it's the story of a middle-aged white guy with no obvious dysfunctions or ghosts in his closet. What James Sterba does have—and has in abundance—is charm, humor, and a wonderful gift for capturing the rhythms and pleasures of July days whiled away on the Maine coast. Sterba is great company on the page, and Frankie's Place succeeds, like no other book I know, in getting the quotidian glories of a New England summer between two covers."

—Michael Pollan, author of The Botany of Desire and Second Nature"

"Frankie's Place is quite simply a joy to read—a portrait of a place, a way of life, and a marriage, by a reporter who turns out to be the world's last extant romantic. Not to mention a great natural cook—who gives us, in addition to everything else, his recipes."

—Joan Didion

"Every word of this wonderful love story speaks of solid, old-fashioned ideals. It is an honest, often hilariously funny book that tells a love story you'll not soon forget. A selection of curious, downeast recipes is an added lagniappe."

—Peter Duchin, author of Ghost of A Chance: A Memoir

"Frankie's Place has tremendous natural charm; it's the witty and wonderfully observed narrative of a summer's action Down East. It should fit very nicely into anyone's beach bag, though it helps if you're attracted to islands, Maine lore, lost fathers, the absurdities of the reporter's trade, and love stories."

—Ward Just

"Jim Sterba made his name as a courageous foreign correspondent -- a restless, gifted journalistic explorer. But in the middle of his odyessey the wind changed, and, most extraordinarily, he found his way home. We can't all be so fortunate, but we can do ourselves the favor of reading Frankie's Place."

-Michael Janeway

On the Maine Coast, Tides of Contentment

'Frankie's Place: A Love Story' by Jim Sterba

By Carolyn See,

The Washington Post

Friday, July 18, 2003; Page C04

FRANKIE'S PLACE

A Love Story

By Jim Sterba

Grove. 274 pp. $23

It's hard not to sound sappy writing about this book. On the other hand, it

would be easy to dismiss the book itself as sappy -- a bucolic memoir of two

middle-aged writers rubbing along happily together for a series of summers on

the island of Mount Desert, off the coast of Maine. "Frankie's Place" is an

understated recollection of "typing" (as Sterba's wife, Pulitzer Prize-winning

Frances FitzGerald, calls her work), hiking, swimming, doing chores, taking

turns cooking, growing increasingly irate at encroaching developers and wacky

next-door neighbors intent on building a Maine version of the Taj Mahal.

But there's a strong element of fairy tale here. Although Sterba has had an

accomplished career as a journalist with the New York Times and the Wall Street

Journal, he presents himself as an Everyman: He was poor growing up; his father

left (or was pushed out of) his life; his stepfather was a bit of a crank. So

how -- in all senses of the phrase -- did Sterba manage to get so lucky?

(Because his wife, besides having won that Pulitzer, comes from a very old and

posh American family: Frankie's mother was the socialite Marietta Tree, nee

Peabody.) Frankie grew up in castles; she's beautiful, rich and smart. And here

he is, getting to hang out with her at her summer place over a long courtship

and then a marriage, in a place that could be Eden itself.

Sterba is nothing if not reserved. He doesn't tell the reader how or why he and

his wife fell in love; instead, he makes gentle fun of the Spartan guest rooms

at Frankie's cottage. He groans mildly about the fascist exercise regimens she

puts him through. He wanders down to the local library and finds out (or lets us

find out) about the Peabody family through books instead of through her. He

never physically describes his wife and very seldom quotes her. He lets images

speak for him: At the beginning of the particular summer, he chooses to remember

how the couple would head out to Somes Sound, out in chilly nature, strip naked,

hesitate, then jump into icy coastal waters.

It's the moment before they jump that counts: Is this going to be agony or fun?

Above all, is it going to be worth it? It's a jump they repeat every day they're

in Maine, that moment -- here I go, being sappy -- of jumping away from relative

comfort into the dangerous waters of a relationship.

In "Annie Hall," the Woody Allen character famously remarks that he can't be

happy until everyone else in the world is happy (and, of course, that's not

going to happen). It's as if Sterba and FitzGerald took that equation and set it

on its head; i.e., the whole world is never going to be happy unless we get

busy, do our own part and set about creating some happiness of our own.

It's not as though they're unacquainted with the tragedies of the larger world.

FitzGerald's "Fire in the Lake" examines the debacle of America in Vietnam;

Sterba was so close to Tiananmen Square that he saw the boy standing, frail and

brave, in front of that tank. But there's another wavelength of life to be

attended to that has to do with putting together a stew with mussels you've

gathered and cleaned yourself. Or shopping for fresh vegetables. Or getting the

old car fixed up so that it turns from a jalopy into a work of art.

It would be so easy to let routine friction take over. Frankie would seem to be

rich, Sterba would seem to be not: He turns this into a joke, searching their

snobbish Swim Club for "snooty Philadelphians," finding the place filled instead

with rather decent people. He has been fleeing from parts of his own sad past

(he only hints), but he's reunited with his long-lost dad and he comes to see

that his father, too, turns out to be a decent sort. Frankie, herself, seems

chary of happiness. Again, Sterba makes a mild joke of it. She'll only serve

lobster perhaps three times a summer, and even then, skimp on the butter,

perhaps because experienced bliss inevitably leads to the possibility of its

loss.

Or maybe not. Maybe the nights and days can stretch out in continued peace.

Maybe the miscreant who dents their car will never get nabbed by the police but

maybe it doesn't matter. Maybe the nouveau riche palace that someone's building

next door will ruin their paradise, or maybe it won't.

Having a little boat and naming it Scoop after the classic Evelyn Waugh novel of

journalism is nice. (Including a spoof of those crazy newspaper cablegrams that

Waugh's editor in chief tormented his foreign correspondent with is nice, too.)

Having too many fresh tomatoes around the house and finally deciding to throw

some out is splendid proof of abundance. See? It might be a sappy book. Or

"Frankie's Place" could be a complex rebuttal to the theological concept of this

Earth as a vale of tears.

© 2003 The Washington Post Company

Liz Smith's Column, June 12, 2003:

LET ME recommend a book now that just might take your mind off your troubles. This is a love story titled "Frankie's Place," written by the husband of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Frankie FitzGerald — one Jim Sterba.

Anyone writing a memoir would be proud to have written this one in particular. It's the story of the Frankie-Jim romance and takes place mostly on the secluded Maine coast near icy Somes Sound. Punctuated with fabulous home-grown recipes by the naturalist-cook Sterba, it offers a kind of Hepburn-Tracy love idyll, punctuated by mussels found in the Sound, dripping fir trees, armies of marauding mice, cars held together with bailing wire, sailboats and put-puts and two writers locked together in their love of nature and fine words. I've never read anything quite like it. It'll make you very happy unless you are too saturated with our celeb/sex/drugs/rock'n'roll rap culture to tell the difference.

Some of my favorite parts include the dangerous deadly mushroom chapter, the differences found by correspondent Sterba between toiling for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, the FitzGerald-Peabody edict against eating lobsters except on special occasions and so much more about Bar Harbor, Northeast Harbor and environs.

This little book is the "find" of a year fraught with death and taxes and 21st century uncertainty.

Portland Press Herald, June 8 2003:

Dozen Maine summers roll into one at ‘Frankie’s Place’

By JOHN ROBINSON,

Some people write for money, some for recognition, some for obscure personal motives or even revenge. Jim Sterba has written an ode to Mount Desert and summer living out of love. It is a love first and foremost for his partner Frances FiztGerald, as well as a careful portrait of the social mores that guide the inhabitants of Northeast Harbor’s wealthy summer colony.

Sterba’s prose is sharp, his facts accurate, his reporting backed up by research and double-checked with those in the know. He learned his trade by working for the New York Times for 16-plus years before heading over to the Wall Street Journal. His explanation behind jumping corporate ships is so detailed it might make some readers think about switching their daily subscriptions. Told with the guileless voice of a Midwestern farm boy made good, Sterba recounts the events of more than a dozen summers spent in Mount Desert through the lens of just one. It begins like all the others, with a plunge in the ocean, and ends unlike others, with a commitment to be buried in that quasi-holy land. Frances FitzGerald is Sterba’s guide to mysteries of Mount Desert and his muse. She has won a Pulitzer Prize for “Fire in the Lake,” she is elegant and beautiful, her family is known to anyone with a passing knowledge of the society pages. How does she do it? And why has she chosen to hang out with him? Through an exploration of Maine in the summer, the author of this engaging memoir seeks to find the answers. Sterba learns, for example, that lobsters are not everyday fare. Among the rusticators seeking a healthy lifestyle, “ lobsters were a reward for good works and achievements big and small, but tending toward the big over the years of monitoring our lobster intake, I noticed that it was an extremely rare summer in which we ate lobsters more than three times. I reported these findings to Frankie on a regular basis, to no effect.” He cultivates a taste for the obligatory Volvo, the accompanying Boston Whaler and lunches at the swim club. Better to woo his love, Sterba learns to cook mussels, beans, corn, mushrooms and other summer fare. He includes the recipes in the book just in case the descriptions make your mouth water. The more Sterba learns about Northeast Harbor, the more he seems to understand himself. An exploration of the FitzGerald family in the local library mysteriously leads to an unexpected reunion with his own long lost father. As he puts his owns ghosts to rest he is more capable of loving his new spouse and, it seems, she is more open to him.

This well-written, light-hearted memoir might not give you anything you don’t already have. For those in the know, it’s kind of like an insider’s guide to Northeast Harbor. For those looking for a nice treat, it is a pleasant way to spend a few hours reading about Maine, writers and the society they frequent.

John Robinson is a free-lance writer who lives in Portland.

From Publishers Weekly, May 12, 2003:

STARRED REVIEW

*FRANKIE’S PLACE: A Love Story

Jim Sterba. Grove, $23(288p)ISBN: 0-

8021-1747-3

Rarely does a subtitle describe a book so well as this one encapsulates journalist Sterba’s experiences at the New England cabin of his friend, fellow writer and Pulitzer Prize-winner Frances “Frankie” FitzGerald. This is a work suffused with love of every stripe, from the romantic kind to the kind one might feel for a place, a way of life and a really good dinner. Although memoirs that arise from such contented sighs are sometimes overly sentimental, Sterba’s journalistic edge keeps the prose far from mushy. It also make for a strange yet delightful combination of elements. Mixed in with his tale of falling in love with Frankie are memories of his days reporting on Asia for the New York Times and the Wall Street Journal, thoughts about lobster and descriptions of prosaic events like brushing his teeth or reading the New Yorker. There are also some recipes that are probably best cooked at a cabin in Maine, after a bracing swim or a stroll through a town store that still sells penny candy. Sterba is a practical romantic who can dream away an afternoon on a sailboat but still hold a lively conversation about how tripartite boat ownership necessitates a concensus during an extensive naming session for the craft. As his relationship with the boat, Maine and cooking unfold over the course of one summer, so too does his romance with Frankie, all of it taking on the same vacation-like pace that’s suffused with leisure but quickens with bursts of activity. This is a beautiful memoir, giving a glimpse not just of a person but of a time and a place worth noting. Agent, Robert Lescher (July)

Forecast:Blurbs from Joan Didion, Tom Brokaw and David Halberstam, combined with release in the middle of vacation book reading season, should help this sell strongly.

From Kirkus Reviews May 1, 2003:

Starred Review

Journalist Sterba (Wall Street Journal) glowingly recalls Mount Desert, a Maine island where her and his wife, writer Frances FitzGerald, spend their summers.

The cabin, surrounded by cedars, spruce, and pine trees, overlooks a fjord; an alternative view features seabirds and lobster-trap buoys. It’s full of books (as befits two authors) and also contains a fireplace made from local granite and a life-sized golden Buddha from Vietnam. Sterba came to the island in 1983 as FitzGerald’s weekend guest. The “entertainment” – better known as the FitzGerald Survival School – included jumps into the ocean’s icy waters and “walks up and down mountain that would have been called forced marches in many of the world’s armies.” But he survived and was invited for another weekend that fall; the next summer FitzGerald invited him for a week. They began seeing each other in New York and eventually married. Although the story takes place over one summer, each chapter includes delightful tangents: Sterba’s early years as a cub reporter with the New York Times, the art of mushrooming, the history of the island and its occupants. The author reminisces about the island’s chief librarian and part-time police officer, probably the only person in the area “working a working knowledge of both the Dewey decimal system and the police response code.” We also meet the poem-writing editor of the local paper (“Why doesn’t the woodpecker / Rattle his brains / When he hammers a tree / Or the windowpanes?”) and a freelance author with a secret past. (He starred in The Texas Chainsaw Massacre.) During the warm summer days, Sterba listens to marine radio (tracking rescue operations), the weather report, and the musings of lonely fishermen. Friends come to visit and are fed; recipes are recorded. The author’s prose is lovely, his self-deprecating humor endearing. Eventually, the summer and the book wind to a close: back to the real world, but not without a sigh of satisfaction.

The perfect summer read about an exceptional summer destination. (Agent: Robert Lescher)

A *star is assigned to books of unusual merit, determined by the editors of Kirkus Reviews.